Thayer's Gull Larus glaucoides thayeri

Critical review currently favours treatment of thayeri as a subspecies of Iceland Gull L. glaucoides (IOC 13.2). It's identification is potentially problematic, but claims are welcomed by BBRC if accompanied by detailed notes and good photographs; details of a ringed or marked bird would of course provide additional evidence. This subspecies breeds in the Canadian arctic from Banks Island to South Ellesmere and Baffin Island, south to north Southampton Island and northwest Greenland. It winters on the Pacific coast of north America from British Columbia south to California and northern Mexico.

| Site | First date | Last date | Count | Notes |

| Elsham Wold | 03/04/2012 | 18/04/2012 | 1 | 2CY bird |

Finder’s Report: Thayer’s Gull Larus thayeri 2nd calendar year bird at Newland Hill, Elsham from Apr 3rd-18th, 2012, first county record.

by Tom Lowe

I can’t resist a roadside flock of gulls, regardless of season or location. My inner optimist always believes there could be something good lurking amongst the locals - and if there is a tanker in the field, I will rarely fail to stop. That tell-tale trailer usually means the field is being treated with liquid waste, and experience has told me that gulls love it. And so it was that early on Monday 2nd April 2012, I sped up the outside lane of the A15 in Lincolnshire past just such a field of gulls and a tanker… and I didn’t stop. I had outdoor work to do and the fine weather was not forecast to last, so I resisted the urge to mount the verge and continued on my way to a farm a few miles further north. It began to look like I’d made the right choice when, a couple of hours later, I found a passage Great Grey Shrike chasing bumblebees on the farm. But there was also a constant passage of large gulls overhead, apparently commuting between the Humber and fi elds to the south where I’d seen the tanker. A niggling temptation stayed with me all day…

The following morning, the gulls were again filing south, in numbers greater than I’d seen all winter, so after I finished work at lunchtime I went after them. I arrived at the fi eld with the tanker in, on Newland Hill near the village of Elsham at about 1.45pm, and was thrilled to see over 600 large gulls, mainly Herring Gulls, feeding avidly. They would not let me get anywhere near them though, always taking flight when they saw my car approaching, so I resorted to scanning a smaller flock in the fi eld to the south. Here, some 200 birds were loafing after feeding, and things seemed a little more settled.

As it was early April, I was hoping for a late Glaucous or Iceland Gull on its way back north, or maybe a Caspian Gull amongst the sprinkling of recently-returned Lesser Black-backs. After 20 minutes, I hadn’t found anything of interest but just as I was considering trying the feeding fi eld again, my scope panned onto a remarkable looking juvenile gull that must have just landed at the front of the flock. It almost looked like it was made of chocolate! My initial reaction when confronted with such a smooth, dark-bodied bird was American Herring Gull, but within seconds I had discounted that species on size and structure. First impressions were of a bird that was slightly smaller than most of the Herrings around it, with a velvety mud brown body and head, fully juvenile upperparts, and long blackish primaries. The bill was dark, and the head was small and rounded, and structurally there was a superficial resemblance to Iceland Gull… could it be a Thayer’s?

As I hastily grabbed some digiscoped shots, the bird walked into the flock and took up a position that allowed only the most obstructed of views. However, amongst the other members of the flock, its distinctiveness could be fully appreciated, and comparisons made with nearby birds. The size and shape seemed to vary according to posture, and when sitting down on the bare earth it could appear surprisingly big. When stood amongst Herring Gulls, though, it was a slim and long-winged bird, with a slender neck and small head which tapered into long lores and a fairly long bill. On some views the bill looked quite narrow, but on others it appeared to thicken at the gonys and look somewhat blob-tipped. Basally the bill was a very dark maroon, whilst the distal third was black. It was not especially long-legged, but the legs were stout and a slightly deeper pink than those of the surrounding Herring Gulls.

Having initially appeared solidly coloured on the head and underparts, closer inspection showed there to be a degree of paler mottling on the breast, and the crown was in fact finely streaked with white. There was also a lick of white along the end of the lores, where the feathering met the bill. The ear-coverts were solidly dark brown and highlighted a fi ne white crescent below and behind the eye, and a hint of a pale ear-covert spot. The eye itself was large and dark, the iris appearing to be a very dark chestnut brown, and was set forward in the head, creating the oft-quoted “soft expression”.

The nape and upper mantle were smooth brown, leading into lower scapulars with a distinctive pattern: a narrow creamy-white fringe bulged in along the edges of the feather to create an oakleaf effect in the solid brown centre, the tip of which was very slightly darker. A pattern of brown and creamy-white chequering was visible on the lesser and median-coverts, as well as on the inner greater coverts, whilst the outer greater coverts were more solidly brown with pale marbling. The tertials were a slightly darker brown with finely patterned edges to the distal half of each feather, lacy-looking tips and some simple internal markings consisting of a creamy white crescent near the tip of each web. At rest, the primaries were blackish-brown with a distinct whitish fringe around the tip of each feather.

Feeling increasingly confident that I was indeed watching a Thayer’s Gull in a field in Lincolnshire, I was desperate to see the spread wing pattern. I needed to see the bird preen, stretch, or fly, and I sat with my finger poised above the video-record button of my camera for an hour and a half before the battery died. Ten minutes later, the bird flew over the hedge into the feeding field. On that fleeting view I glimpsed a pale, silvery underside to the primaries, and a very pale inner primary window on the upperwing, flanked by darker outer primaries and secondaries, but then it was gone, with no detail seen, and I couldn’t relocate it. Would it show the characteristic “Venetian blinds” primary pattern of Thayer’s Gull, or would it be curtains for it and me? I spread the news of what I had seen, and that evening, uploaded my best images of the bird to the internet.

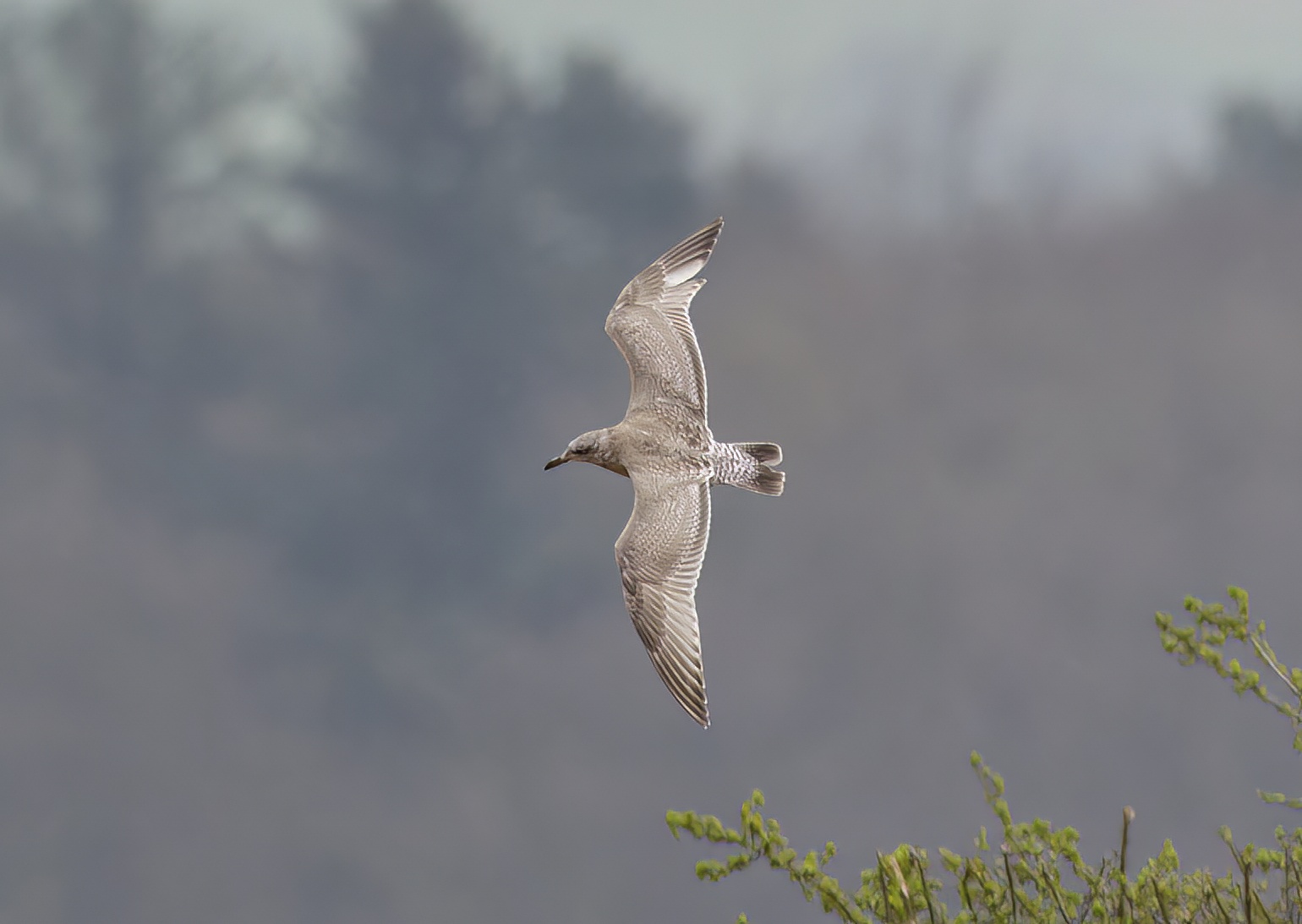

Following a night spent looking at images of near-identical birds on the internet, I woke on 4th April to sleet lashing my window on a near-gale force north-easterly, and hopes of relocating the gull were dashed. There were barely any birds in the fi elds, and the previous days’ overhead passage of gulls off the estuary had ebbed to a mere trickle. In such inclement weather, it appeared they weren’t venturing far from their Humber slumber. By mid-afternoon, however, the rain eased, and a couple of intrepid souls followed up the tentative pager message of the night before. The gulls were back too, and at 3pm the bird was refound, using the gale to “dip-feed” over the field, showing that critical wing-pattern to great effect. A couple of blasts of the Catley cannon, and the definitive photos were in the bag: P5-10 showed dark outer webs and contrastingly pale inner webs, with the dark curling around the tip of the feather in the manner of a Nike “tick”. Rather helpfully, on the right wing P5 was missing, and P6 was visible in its entirety, as if laid out on a museum table. P1-4 showed a ghosting of the same pattern, but with the addition of a long pale lozenge shape running along the outer web, effectively making the whole feather appear pale except for an isolated darker tip to the outer web. The secondaries also showed a pattern of dark outer webs and pale inner webs, but as they tend to be held more tightly together, the general impression was of a solid dark brown bar, similar in colour to the outer primaries, with a broad pale trailing edge. From below, the remiges were pale and silvery with contrasting dark tips to P5-10 forming a bar along the wingtip. The underwing coverts and axillaries were dark brown. A feature that took our little group by surprise was the forked tail, something we hadn’t expected to see; a few central tail-feathers were missing, breaking up the broad, muddy brown tail band. There was pale notching and marbling on the bases of the outer three or four feathers, and the rump and Uppertail coverts were heavily barred brown. Similar dense barring was visible on the undertail coverts.

Despite its extreme rarity, and the fact that nearly every Thayer’s Gull on this side of the Atlantic has attracted controversy of some sort, here I was claiming one in a field in Lincolnshire! Yet the combination of size, structure and the suite of plumage features I had now been able to observe and that had been photographed left me feeling this had to be the real thing. Not only did everything appear to stack up, but it was also at the darker end of the Thayer’s spectrum (immediately bringing to mind photos of the Danish bird in 2002) which helped to rule out thoughts of Kumlien’s Gull. My confidence was buoyed by positive comments from friends that I had emailed photos to, and over the next few days, it was successfully twitched by many. Its appearances became very erratic, but after a few days of absence, I relocated it on 17th April, and it remained until at least 18th. Although most observers were happy with the identification, the bird inevitably attracted its share of internet discussion and a variety of opinions were voiced. The possibility of a hybrid was something I had considered, but could a hybrid really match so many Thayer’s Gull features so closely? The overall smoothness of the body plumage is something only really associated with American Herring Gull or a few Pacific coast species and hybrids, and whilst hybrids are fairly common there, they are apparently undocumented on this side of the Atlantic. With all these things, likelihood of occurrence surely has to play a part in the discussion, and following a winter that had seen an unprecedented influx of Iceland and Kumlien’s Gulls into western Europe, it seems only fitting that a Thayer’s Gull or two should join the party. As well as my own digiscoped efforts, there were a great many photographs taken of the bird, many of which aided in the identification process. I have attached a selection; others can be seen online:

http://pewit.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/thayers-gull-lincolnshire-fi rst.html

http://pewit.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/thayers-gull-batch-2.html

http://www.rarebirdalert.co.uk/RealData/gallery.asp?level=4&SpeciesID=5980.2

References

AOU Committee on Classification and Nomenclature (North & Middle America), comments on proposals 2017-C. http://checklist.aou.org/nacc/proposals/ comments/ 2017_C _comments _ web.html#2017-C-7

McGowan, R.Y., and Kitchener, A.C (2001). Historical and taxonomic review of the Iceland Gull Larus glaucoides complex. British Birds 94(4): 191-5.

Snell R.R. (2002). Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides) and Thayer’s Gull (Larus thayeri). No.699 in The Birds of North America, A. Poole and F. Gill (eds) Philadelphia: Birds of North America Inc.

(Account as per new Birds of Lincolnshire (2021), included September 2022)

(Account prepared September 2019; includes all records to 2018)